Street Fighter and The King of Fighters in Hong Kong: A Study of Cultural Consumption and Localization of Japanese Games in an Asian Context

by Benjamin Wai-ming NgIntroduction

The electronic game is one of the most globalized but little-studied forms of Japanese popular culture.[1] Japanese arcade games, home console games and handheld console games have dominated the world market since the mid-1980s. [2] Hong Kong is one of the consumption centres of Japanese electronic games in Asia. As John Fiske points out that just as readers can become "active readers" by adding new meanings to cultural products (Fiske 1989, p.32), Hong Kong game players, businessmen and artists have been turning Japanese games into Hong Kong-style Japanese games and other forms of hybrid culture in terms of the rule of playing, the making of crossover cultural products as well as specific languages translated, used or created. As one of the first studies on the subject of Japanese games in Asia, this paper examines the reception and domestication of Japanese games in Hong Kong through a case study of Street Fighter (SF) and The King of Fighters (KOF), the two of the most popular arcade games as well as combat games in the world. & #12288;Both games have had a significant impact on Hong Kong popular culture and the Hong Kong entertainment industry. Hong Kong artists and players have been selectively and creatively incorporating elements of Hong Kong commercial movies, martial arts novels and comics, as well as lower-class slang and behaviour into these two Japanese games. Examining the history of SF and KOF in Hong Kong, the making of new rules and jargons by Hong Kong players, and the adaptation of these two games into Hong Kong comics from historical and cultural perspectives, this study aims to deepen understanding of the dynamic force of localization and transnational cultural flows in forging Asian popular culture. Data about SF and KOF were gathered from newspapers, magazines and the internet, interviews with game players, arcade game shopkeepers and editors of game magazines, as well as on-site observation and participation.

The History of Street Fighter and The King of Fighters in Hong Kong

The history of Japanese arcade games in Hong Kong can be traced to the 1970s. In these early years, small game centres equipped with first-generation arcade games such as Pac-Man and Space Invaders mushroomed across the entire territory. In the 1980s, Japanese games became dominant at Hong Kong game centres. In 1987, Capcom, a leading Japanese game software company, introduced Street Fighter (SF1) to Hong Kong and it became an instant success. Newman (2002) argues that "the pleasures of videogame play are not principally visual, but rather are kinaesthetic" (p. 2). This idea can be applied to SF1. Despite its primitive program and character designs and unsophisticated graphics, SF1 won the hearts of the players with an innovative control system (such as the use of separate keys for punching and kicking and the joystick for choosing direction, jumping or hiding) that later became the model for other two-dimensional combat games including the KOF and Samurai Spirit series. Street Fighter's draw also helped popularize the term hissatsuwaza (literally "sure-kill technique", the most powerful fighting skill) among young people in Hong Kong. [3] Game players in Hong Kong added elements of Chinese martial arts to SF1 by perpetuating the rumour that there was a hidden hissatsuwaza called yiyangzhi (single yang finger), a term borrowed from popular Hong Kong martial arts novels by Jinyong. There was a time when Hong Kong game players were absorbed with finding and discussing this hidden move. This shows that the localization of Japanese combat games started from the very beginning of their introduction to Hong Kong.

Street Fighter 2 (SF2), launched in 1991, created an unprecedented arcade game craze in Hong Kong. The game represented a breakthrough in control system, stage and graphic designs, drawings and music (Kent, 2001). It became the most popular arcade game in Hong Kong in the early 1990s. Many small-sized game centres had nothing but SF2 games. The queue was always long for SF2. Street Fighter 2 competitions were held frequently by various organizations in different parts of Hong Kong. Local game magazines focused their reports on SF2. Characters and terms of this game were adopted in Hong Kong comics, movies and Cantonese pop music (Chen, 2002). For example, the Hong Kong comic artist Situ Jianqian, used Ryu, Ken and Chun Li, the three major characters of the SF series, in his comic, Supergod Z: Cyber Weapon (1993). After receiving a warning letter from Capcom, Situ changed their names, but kept the character designs (see Figure 1) (Situ, 1993).

Figure 1. Supergod Z: Cyber Weapon borrows the main characters from SF2

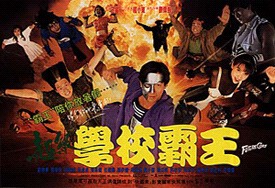

Likewise, the Hong Kong movie, Future Cops (1993) directed by Liu Weiqiang, copied the story and characters from SF2. Arron Kwok and Ekin Cheng, two top Hong Kong movie actors, played the role of Ryu and Ken, respectively (Figure 2). Even the fighting tactics of the movie followed the game closely.

Figure 2. Future Cops is the unlicensed Hong Kong movie edition of Street Fighter

Jumping on the bandwagon of the SF craze in Hong Kong, helped the movie pocket 1.8 million HKD at the box office. In addition, City Hunter (1992, directed by Wangjing, starring Jacky Chan) stole the music from SF2.

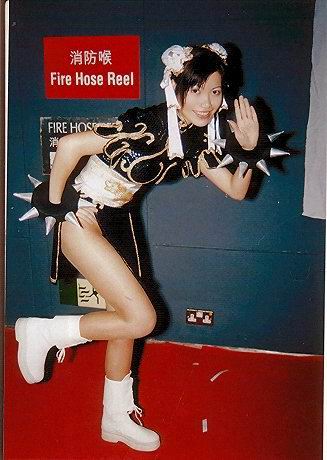

Hong Kong businessmen and game players, without the permission of Capcom, created a number of modified versions of SF2 with stronger combat ability. Street Fighter merchandise such as figurines, T shirts, posters, music CDs and card games, licensed or not, flooded the market. Main characters of SF, including Ryu, Ken, Chun Li and Gouki, became household names and cyber icons. Chun Li was one of the most favourite characters for "cosplay" (or "costume play", a Japanese-English term coined to refer to the dressing of ACG (animation-comic-game) lovers as their favourite ACG characters) (see Figure 3). A Hong Kong young man was hospitalized for chemical poisoning, because he used the hair spray too much and too often to copying Ryu's hairdo.

Figure 3. Chun Li has been a favourite character for cosplay in Hong Kong since the 1990s

Having reached the peak of its popularity and influence in Hong Kong in the early 1990s, the SF craze began to cool down and was later overtaken by KOF in the late 1990s. A brief revival occurred in 1997 when SF3 was launched. Street Fighter 3 has enhanced combat ability and new characters. Besides the original SF series, Capcom also introduced SF-related series, such as Young SF series, EX SF series and SF versus KOF series for arcade games. After the launching of SF EX3 in 2000, Capcom announced that it would cease the production of SF arcade games. However, SF has not disappeared from Hong Kong. Diehard SF fans turn to play SF games adapted for PS2, the leading home console system, as well as continue to play old SF arcade games (in particular SF2) and participate in SF tournaments.

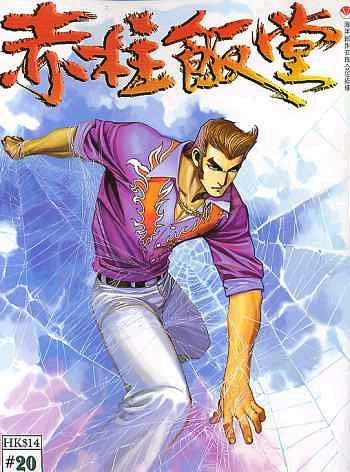

Developed by SNK, a Japanese game developer specializing in combat games, KOF has been introducing a new series annually since its introduction in 1994. In the late 1990s, KOF replaced SF as the most popular combat game in Hong Kong. When KOF was first launched in Hong Kong in 1994, its response was overwhelming. Many game players found the team format (three fighters vs. three fighters) adopted by KOF more exciting than the individual fighting format used in SF. KOF reached its peak in the late 1990s, and in particular the KOF 96, KOF 97 and KOF 98 created a commotion. Many local organizations and game centres organized KOF tournaments. Its main characters, such as Iori Yagami, Kyo Kusanagi, Mai Shiranui and Laqia, became well-known among young people in Hong Kong. The character design of KOF has had an impact on Hong Kong youth fashion and comic design. For example, the so-called "MK look" fashion style is under the influence of the KOF character designs. In recent years, the "MK look" has penetrated Hong Kong street fashion and combat comics (Figure 4). The demand for KOF character goods, both imported and locally made, was fierce and included Hong Kong editions of Japanese KOF comics and guide books, action figures and weapons designed by the Hong Kong comic artist Situ Jianqian, as well as KOF comics, magazines and guide books published in Hong Kong.

Figure 4. The "MK Look" in the Characters in Stanley Kitchen by Wen Ri Liang

The popularity of KOF began to decline after the Millennium, but it remains the most popular combat game at game centres in Hong Kong. For example, Fight Club, an unofficial KOF fanclub founded in 2001, has developed into the largest game organization in Hong Kong with 30,000 members (Figure 5) (Wong, 2004). The main reason for the decline of KOF is that it has been using the same circuit board for more than a decade, making the game inferior in graphic and sound effects when compared to its Capcom and Namco counterparts. Besides, the quality of KOF deteriorated after the bankruptcy of SNK in 2000. In 2000, SNK merged with the Korean game maker Playmore to become SNK Playmore. In celebrating the tenth anniversary of KOF and rekindling people's interest in the game, in late 2005, SNK Playmore introduced KOF 11, the next-generation KOF arcade game that uses a brand new circuit board. It has also developed the home console game market by introducing the KOF: Maximum Impact for PS2 and SNK versus Capcom for Xbox.

Figure 5. A KOF Tournament organized by the Fight Club in 2004.

In retrospect, from the earliest SF1 to the latest KOF11, the twenty years of Japanese combat games in Hong Kong have become an integral part of the collective memories of Hong Kong players. The SF and KOF series will enter the Hall of Fame in the history of games in Hong Kong. Although these two games are now past their prime, they remain popular and influential within and outside of the world of games in Hong Kong. The history of the two games demonstrates the interplay of Japanization and localization in making Hong Kong-style Japanese games. The games themselves are imported from Japan and their functions are built-in, and thus have little "cultural discount" by nature (Hoskins & Mirus, 1988), but Hong Kong players and artists have used different tactics to play, interpret and use SF and KOF in their own ways. This important theme will be further developed in the next sections.

Street Fighter and The King of Fighters in the Making of an Arcade Game Culture in Hong Kong

If games are a form of text, then the game players in Hong Kong are "excessive readers" (in John Fiske's terminology) who actively interpret the text in their own ways based on their life experiences (Fiske, 1989). Since the early 1990s, Hong Kong players have established a unique arcade game culture by setting rules and jargons almost exclusively used among themselves in Hong Kong.[4] These rules and jargons were created during the age of SF and reinforced by KOF and other combat games. They have gradually been adopted into non-combat games and even the daily life and vocabulary of the young people. Hence, consuming Japanese games in Hong Kong is not a form of cultural imperialism, because we have witnessed the making of a dialectical nexus between global (Japan) and local (Hong Kong) in terms of ongoing cultural hybridization (Tomlinson, 1997).

The majority of combat game-related jargons borrow from the languages of the lower class and some are considered indecent and coarse by society. The background of the players and the running of game centres are accounted for the influx of the lower-class language into the arcade game culture in Hong Kong. In the 1980s and 1990s, most game centres in Hong Kong were small-sized and financially weak. They preferred SF and KOF games because of their small size and high return rate. They were mostly located in the old districts where rents were cheap. Hence, most players came from the lower class living hereby including students, manual labours and even juvenile delinquents. The image of game centres perceived by the officials, teachers, parents and the press was relatively negative, associated with smoking, excessive noise, gang activities, and drug dealing. Unlike their Western counterparts (Greenfield, 1984), few people in Hong Kong recognised the educational and cultural values of electronic games. Playing at game centres was regarded by the public in Hong Kong as a form of entertainment for lower-class and uneducated males (Tam, 2001). [5] As young people from poor families could not afford a game console or PC, they played at game centres. Consciously or not, the players introduced their languages into arcade games. Table 1 lists the jargons added into the Hong Kong arcade game culture during the heydays of SF in the early 1990s:

Table 1: Cantonese Game Jargons Created or Adopted by SF and KOF Players in Hong Kong

| Jargons | Original Meanings | Derived Meanings | Popularity and Uses |

| "Da-bau-kei" or "bau-kei"(literally "exploding the machine") | Da-bauis a coarse Cantonese expression that means breaking or destroying. | Completing the entire game program such as destroying all enemies or reaching the destination. | It has become a popular term for young people in Hong Kong. Many terms have been derived from it, such as "bau-kei-wong" (a skillful player who often wins the game), "bau-kei-kung-loek" (the tactics to win the game) and "bau-kei-wa-min" (the picture with congratulatory notes displayed on the screen when the player finishes the game). |

| "Da-dai-lo" (literally "beating up the big brother") | "Dai-lo" means the elder brother. It also applies to the gang leader. | Fighting with the last (usually the strongest) opponent. | It has become a jargon for all games. Many terms have been derived from it, including "Chung-dai-lo" (the strong opponent in the middle of the game), "yan-chong -dai-lo" (hidden opponent, usually extremely powerful) and "lam-mei-dai-lo" (the last opponent). |

| "Hissatsuwaza" (literally "sure-kill technique") | A Japanese term originally applied to the strongest tactic in martial arts. | The killing tactic and weapon used in combat games | This term has existed for decades, but the SF series popularized it. It is now a common term used in daily conversation whether or not the conversation is related to games. |

| "Chek-chau" (literally "one-to-one weapon-free combat) or "dan-tiu" (literally "challenge by one & self") | A gang slang that means one-to-one combat. | One-to-one competition | This term has been used for a long time and is later applied to SF and other combat games. |

| "Cheo-bo" and "cheo-sing" | Both terms were coined by Hong Kong players and refer to tactics--"bo-tung-chun" ("fireball-throwing fist') and "sing-lung-chung" ("rising-dragon fist"-- used by Ryu in SF. | Any flying weapon and hitting tactic. | They have become jargons for combat games. |

| "Bug-kei" & #65288;bug & #25216; & #65289; | A term coined by Hong Kong players to refer to tricks. | Using the bugs in the program as tactics to play. | KOF has many bugs and thus its players have developed many "bug tactics." This term has become a jargon for all games. |

| "Da-Kwai" (literally "hitting the turtle") | A term coined by Hong Kong players to refer to the defensive tactics. | A kind of "bug tactic" that only plays defence | KOF, due to its design problems, can easily use this defence tactic. This term has become a jargon for all games. |

In addition to game jargons, Hong Kong players have also established a set of rules for arcade games commonly used in Hong Kong. Many of the rules were started from SF and then reinforced by KOF and other arcade games. The following table lists major rules established by Hong Kong players in playing SF and KOF:

Table 2: New Rules Set by the Players of SF and KOF in Hong Kong

| Jargons | Meanings | Rules | Popularity and Uses |

| "Kan-kei" | Booking for the next game. | Put a coin or token at the top of the machine to book for the next game. When the current player finishes his game, he must give up the machine to the next player. | Similar behaviours existed in Hong Kong in the late 1970s, but were not common. The popularity of SF1 made this rule standard practice at game centres. |

| "Tiu-kei" | Challenge other player (usually unknown to each other). | When someone is playing the game, the challenger inserts money in the same machine or nearby machines to challenge. The current player has to stop his game against the computer and must take up the challenge. | This behaviour began with SF1 and became prevalent in SF2 and KOF. It has become a common practice for arcade games that have the challenge function built-in . |

| "Joeng-round" (round) | Giving up one round for the weaker player so that both players can play longer. | For three-round match games like SF, the first round winner loses the second round opponent on purpose so that both players can play the final round and the weaker player does not feel offended. | This rule started with SF1 and soon applied to other three-round games. |

| "Wat-kei" | The use of unfair tactics in the game. | Unsportsmanlike behaviour that relies on "bug tactics" to defeat the opponent. This is a taboo in playing arcade games in Hong Kong. | This behaviour appeared in SF1 and became more common in KOF. Nowadays, this term is commonly used to describe any kind of unfair or unsportsmanlike behaviour or attitudes. |

Influenced by the rules, languages and behaviours of the worlds of the lower class, the martial arts and the underground, the making of game jargons and rules by SF and KOF players in Hong Kong demonstrates the fact that playing arcade games, like watching soccer, is largely a subculture for lower-class males. For example, the common practice of "tiu-kei" (challenging) shows that young people use competition to improve and show off their skills, like the way martial arts students often do. "Joeng-round" (giving in one round), "kan-kei" (booking for the next game) and the ban of 'wat-kei" (using bugs to win) are like underworld rules to reduce unnecessary arguments and confrontations. Interestingly enough, from my own fieldwork in Japan and interviews with Japanese game players, I did not find similar rules among arcade game players in Japan. A Japanese player explained that Japanese culture puts emphasis on harmony and thus most players only play with the machine by themselves or with their friends, adding that Japanese players try to keep a distance from others and usually do not challenge strangers. Accordingly, there is no need to set rules that restrict players from hogging machines or that ban the use of bug tactics. Another reason, from my observation, is that playing at game arcade is a socially acceptable behaviour in Japan and players come from different sectors of society. Thus the rules and languages associated with the lower class and the underground are not incorporated into the games in Japan.

The fusing of elements from the Hong Kong lower class into Japanese games should not be interpreted as a corruption of "Japanese-ness" or authenticity, but a hybrid culture that enriches the content of and adds new dimensions to Japanese games in transnational cultural flows.

The Adaptation of Street Fighter and The King of Fighters in Hong Kong Comics

While the making of new rules and jargons in playing Japanese games represents a kind of localization of Japanese culture from below (consumers, not producers), the adaptation of Japanese games in Hong Kong comics is the localization of Japanese culture from outside (Hong Kong, not Japan).

Hong Kong comics are famous for their kung fu stories and actions. By nature, they are similar to Japanese combat games. Both are about righteous heroes fighting against the evils. In addition, the relatively culturally odour-free SF and KOF make them easier to be indigenized outside Japan. [6] Therefore, adapting SF and KOF into Hong Kong comics is relatively easy for Hong Kong comic artists. Many of them are lovers of Japanese combat games themselves. The making of Hong Kong comic editions of SF and KOF is a smart business idea, since there are a large number of faithful supporters of these games in Hong Kong. According to my count, from 1991 to the present, Hong Kong comic artists have produced at least 65 Hong Kong comic editions of SF and KOF. Many have been serialized and enjoy a good circulation. While borrowing their main characters and fighting skills from SF and KOF, these Hong Kong comics have also added local elements to make them a hybrid culture.

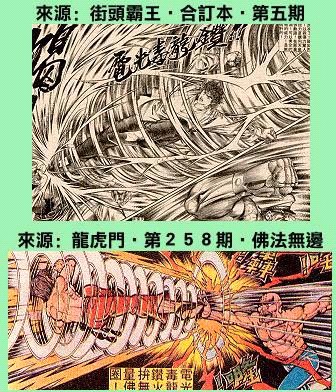

In 1991, the Hong Kong comic artist, Xu Jingchen, published Jietou bawang (Street Fighter, 100 issues), the first Hong Kong comic edition of SF. This comic was an instant success and its first issue sold 50,000 copies. However, it did not acquire the copyrights from Capcom and thus was an unlicensed publication. Since Xu was not under the supervision of Capcom, he could freely add many new elements to SF in terms of storylines, characters and fighting skills. For example, unlike the original story in the game, in this comic, Ryu and Chun Li are lovers and later marry. The comic reaches its climax when all SF major characters, including friends and enemies, come to attend their wedding banquet. Hong Kong readers like this development, because it follows the tradition of Hong Kong martial arts novels of combining romance and action. This comic keeps the main characters and fighting skills of the game, but adds a large number of new characters and martial arts tactics to enrich the story and action, turning the Japanese combat game into Hong Kong-style kung fu comics. Of all the new characters, the most noteworthy is Zhan Hu ("Fighting Tiger") who is obviously borrowed from Wang Xiaohu, the protagonist of the classic Hong Kong fung fu comic, Long hu men (School of Dragons and Tigers) in terms of character design and martial arts (Figure 6). More precisely, Zhan Hu is the middle-aged version of Wang Xiaohu. In early years, Xu Jingchen worked under Huang Yulang and Ma Rongcheng, the two most influential masters of kung fu comics in Hong Kong. No wonder he has applied the storytelling and drawing techniques of Hong Kong kung fu comics throughout his work.

Figure 6. The adding of famous martial arts hero into Hong Kong comic edition of SF.

Due to copyright reasons, Jietou bawang was forced to cease its publication. However, Xu Jingchen soon created another comic, entitled Super Fighter (120 issues) (Figure 7). This comic keeps the main characters of SF, but gives them new names to avoid legal responsibility. For example, Ryu becomes the Savior.

Figure 7. Super Fighters keeps SF major characters.

After Jietou bawang and Super Fighter, Xu Jingchen turned to draw licensed editions of SF comics, including Street Fighter 3 (155 issues), Young Street Fighter Zero 3 (40 issues), Street Fighter EX2Plus (38 issues) and SF vs KOF (2001, 27 issues) (Liu, 2003). Due to the supervision of Capcom, these licensed comics are closer to the original game than his previous works. Even the names of fighting tactics are adopted from the game. Although the degree of creativity and localization are compromised, Xu continues to add new plots and tactics to his comics. For example, in Street Fighter 3, Ryu creates a new tactic, called Chun Li wangqingzhang (The fist of forgetting the love of Chun Li) in memory of Chun Li. This plot seems to have borrowed from the Jinyong's martial arts novel, Shen diao xia lu (The Legend of the Condo Heroes) (Figure 8) (Ba, 2001). [7]

Figure 8. Ryu creates a new fist tactic in memory of Chun Li in the Hong Kong Comic, Street Fighter 3.

Moreover, he continues to borrow the character Wang Xiaohu (renamed as Wanghu) from School of Dragons and Tigers (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Wang Xiaohu becomes a character in the SF 3 comic.

Likewise, in SF vs. KOF, the plot of baby monk he added might have borrowed from Ma Rongcheng's Zhonghua yingxiong (The Legend of Chinese Heroes), a classic of kung fu comics. The drawing of fighting scenes and background follow the Hong Kong comic tradition. In his drawing of hissatsuwaza, Xu's comics keep the original names, but change them into Chinese kung fu instead of simple and straight forward tactics as designed in the original games. The language used is colloquial Hong Kong-style Cantonese with some indecent expressions, such as "da-zan-keio" & #25171; & #27544; & #20322; (beat him up until he becomes handicapped).

Many other Hong Kong comic artists also drew their own editions of SF comics. According to my count, in the 1990s alone, there were at least 15 comic editions of SF made in Hong Kong, including Guang Binqiang' Street Fighter 3 Third Strike (28 issues) and Yu Jianpei's Street Fighter 92 (12 issues). Most of them were unlicensed publications and did not last long. Like Xu's, they were all drawn in the Hong Kong kung fu comic style and added many new characters and stories.

Hong Kong comic editions of KOF have been published since 1995. Situ Jianqian, the artist of Supergod Z: Cyber Weapon, is famous for turning KOF into Hong Kong comics. His works in this regard include KOF Z (2000, 45 issues), KOF 2000 (40 issues) and KOF 2002 (56 issues). In particular, his first KOF comic, KOF Z, sold about 50,000 copies per issue, making it the bestselling Hong Kong comic edition of KOF. From the beginning, Situ has acquired the copyrights from SNK and therefore his comics are relatively faithful to the original. Nevertheless, he has added Hong Kong elements in his comics in terms of drawing and character. For example, there are some new supporting roles who have Hong Kong-style nicknames, such as Dasha & #22823; & #20749; (big fool), Datouwen & #22823; & #38957; & #25991; (Wen, the big-head) and Xixiong & #32048; & #38596; (Xiong, the little).

Xu Jingchen, the most famous SF comic artist, also produced a popular KOF comic, KOF 99 (38 issues). Its first issue sold about 40,000 copies and the rest between 20,000 and 30,000. Deng Yaorong is the artist of KOF 96 (36 issues), KOF 97 (52 issues) and KOF 98 (44 issues) and his KOF 96 sold about 40,000 copies at its peak. In recent years, the most active Hong Kong artist of KOF is the team of Yong Ren and Cai Jingdong who created KOF 2001, KOF 2003 (2004, 8 issues) and KOF Maximum Impact (2005). All of these KOF comics made in Hong Kong have incorporated local elements. For example, in KOF 2003, Hong Kong is the major background and the venue of the KOF tournament is the Hong Kong Convention and Exhibition Centre in Wanchai. Its language is very colloquial and contains some indecent expressions, such as "chun" & #23544; (arrogant) and "da-dou-fei-hei" & #25171; & #21040; & #39131; & #36215; (beat one up to the air) (Figures 10a and 10b).

Figure 10a. Fighting in the famous tourist spot, Golden Bauhinia Square, located in front of the Hong Kong Convention and Exhibition Centre (KOF 2003).

Figure 10b. KOF 2003 is full of Hong Kong-style slang.

In brief, this section indicates that Japanese combat games and Hong Kong martial arts comics are perfectly and creatively mixed into a hybrid cultural form, namely, Hong Kong comic editions of SF and KOF. The localizing and synergetic tactics employed by Hong Kong comic artists show the creativity of Hong Kong artists and have added new life to Hong Kong comics.

Concluding Remarks

If the world is becoming a "global village", this global village must include different tribes. Japanese games have gained global popularity, but they are interpreted and played differently by players according to their own social and cultural backgrounds. Through a study of the reception and local adaptation of Street Fighter and The King of Fighters in Hong Kong, this research is one example of how Japanese games have been localized abroad. It deepens understanding of two important issues regarding cultural consumption and localization in an Asian context.

The first issue involves looking at how individual consumers interpret and consume cultural products in order to add new meanings to them. A historical review of SF and KOF in this article shows that Japanese games have been localized by players in Hong Kong for more than two decades. Like kung fu comics, gangster films and soccer, playing arcade games, in particular its combat genre, is largely a subculture for lower class young males in Hong Kong. These males worship heroism based on eye for eye attitude and brotherhood. Male players like combat games, because they are congenial to the Hong Kong kung fu and street cultures (Ng, 2001). [8] Hong Kong players have borrowed terms, rules and techniques from Hong Kong martial arts novels, movies and the underground world for these two games, and thus domesticating Japanese games so that they can fit in their mode of thought and behaviour. Players cannot change the system, but can modify the rules and vocabulary (Cerdeau, 1984). The idea of passive mass as the slave to cultural industry (Adorno, 1991) is not applicable to SF and KOF players in Hong Kong. Consumers have creatively added new meanings and contents in consuming popular culture (Fiske, 1989).

The second issue involves looking at how cultural importers (or recipients) make use of foreign elements to create their own culture. Street Fighter and KOF have influenced Hong Kong comics, movies, fashion, and character goods. This study focuses on how these two Japanese games are adapted into Hong Kong comics. Hong Kong SF and KOF comics are forms of hybrid culture that mix Japanese games with Hong Kong kung fu comics. [9] This crossover is a kind of hybridity that enhances cultural creativity and vitality (Canclini, 1995). Since 1991, Hong Kong comic artists have been drawing their own editions of SF and KOF in the typical Hong Kong comic style. Names, places, martial arts, language, drawing and format have all been localized. For example, many characters borrow from representative Hong Kong kung fu comics or movies as well as the storylines and plots from bestselling martial arts novels. Colloquial Cantonese including foul languages and gang jargons are used in these comics. Street Fighter and KOF have been transformed into various kinds of hybrid cultural products and in some cases the Hong Kong feel is even stronger than that of the Japanese. Besides, this study suggests that the localization of Japanese games is mainly initiated by Hong Kong artists, businessmen, players and consumers, and not by Japanese companies. Hence, neither glocalization nor cultural imperialism is applicable to describe the nature of the reception of Japanese games in Hong Kong (Robertson, 1995). [10]

The above-mentioned two issues show the powerful tactics of cultural consumption, borrowing, appropriation, localization and hybridization in transnational cultural flows in an Asian context, an important theme that deserves more indepth investigations in game studies in the future.

References

Adorno, Theodor (1991) The Cultural Industry: Selected Essays on Mass Culture (London & New York: Routledge)

Ba, Shenjing (2001) "Cong youxi manhua shuoqi" (Discourse on Games and Comics). Diannao shangqingbao (Journal of Computing Communications), Vol. 7.

Canclini, Nestor G (1995) Hybrid Cultures: Strategies foe Entering and Leaving Modernity. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Certeau, Michel de (1984) The Practice of Everyday Life. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Chen, Dawei (5 April 2002) "Lun Xianggang wuxia manhua de tuibian" (On the Changes of Kung Fu Comics in Hong Kong). Chuantong Zhongguo wenxue dianzibao (E-Journal on Traditional Chinese Literature) (http://www.literature.idv.tw/news/news.htm), Vol. 115.

Fiske, John (1989) Understanding Popular Culture. London & New York: Routledge

Greenfield, Patricia (1984) Mind and Media: The Effects of Television, Vidoegames and Computers. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Hoskins, C and Mirus, R (1988) "Reasons for the U.S. Dominance of the International Trade in Television Programs," Journalism of Communication, Vol. 38.

Kent, Steven (1991) The Ultimate History of Video Games. New York: Three Rivers Press.

Liu, Chilang (2003) "Xu Jingchen qianwan tui jieba" (Xu Jingchen spending millions to promote his Street Fighter comics). Easyfinder, Vol. 506.

Massey, D. (1998) "The Spatial Construction of Youth Cultures," In T Skelton and G. Valentine (Eds) Cool Places: Geographies of Youth Cultures. London and New York: Routledge.

Newman, James (July 2002) "The Myth of the Ergodic Videogame," Games Studies, Vol. 2, Issue 1.

Ng, Benjamin Wai-ming Ng. (2001) "Japanese Videogames in Singapore: History, Culture and Industry," Asian Journal of Social Science. Netherlands: Brill. Vol. 29, No.1.

Roberston, Roland (1995) "Glocalization: Time-Space and Homogeneity-Heterogeneity." In Mike Featherstone, Scott Lash, and Roland Robertson (Eds.) Global Modernities. London: Sage.

Situ, Jianqian (1993) "Preface," Supergod: Cyber Weapon. Hong Kong: Freeman Press.

So, Tin-fai (2002) Internet Dictionary. Hong Kong: PC User.

Tam, Wai-lok (2001) Japanese Video Games in Hong Kong: A Study of Subordinate Males as Consumers. MA thesis, Department of Japanese Studies, National University of Singapore.

Tomlinson, John (1997) "Cultural Globalization and Cultural Imperialism," In A. Mohamadi (Ed.) International Communication and Globalization: A Critical Introduction. London: Sage.

Wong Hingyu (1 December 2004) "The Strongest Underground Combat Game Organization," Eastfinder, Vol. 671